Galapagos Islands Wildlife

Many theories exist regarding the unique nature of the flora and fauna on the Galapagos islands. A popularly held belief is that the original species that evolved into the unique Galapagos variety found their way to the islands on flotation rafts of vegetation and other waste and were carried to the island via wind and sea currents.

Charles Darwin Voyage to the Galapagos

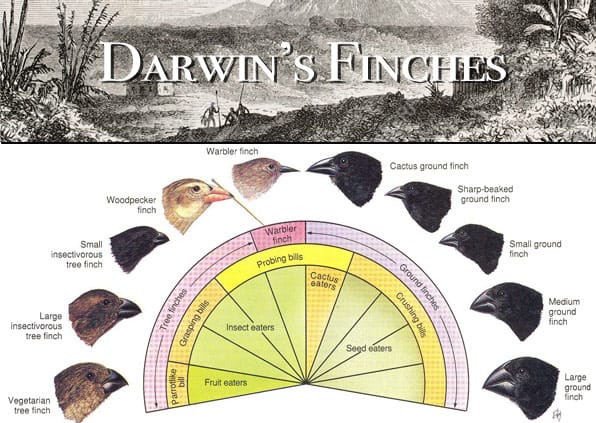

Although he was only in the Galapagos for five weeks in 1835, it was the wildlife that he saw there that inspired him to develop his Theory of Evolution.

What Animals Can You See on the Galapagos?

A wide variety of animals can be found on the Galapagos Islands. The most famous ones that visitors love to see include:

- Galapagos Giant Tortoise

- Land Iguanas

- Marine Iguanas

- The Galapagos Seal Lion

- Darwin’s Finches

- Galapagos Hawk

- And more

What Makes Galapagos' Wildlife so Remarkable?

Compared to the enormity of the Amazon Basin, Galapagos is a very small archipelago lost far out in the ocean. To give one illustration, the Amazon is home to over three hundred species of reptiles: Galapagos has only iguanas, tortoises, lava lizards, geckos and snakes. The total is fewer than ten if you don't count all of the different sub-species and under 25 even if you use the most generous count. Can they really be compared?

The natural value of the Galapagos Islands does not lie in diversity: in fact, it's just the opposite. Galapagos is a harsh, remote land, and the species that arrived there did not survive by diversifying, but rather by evolving specific traits to suit a certain niche in the environment.

Although natural selection takes place all over the globe, nowhere is it more evident than in the Galapagos Islands. It is this status as a "Laboratory of Evolution" and its historical inspiration of naturalist Charles Darwin that make Galapagos special. The Galapagos Islands are also extremely pristine: no other place on earth is as free of introduced and invasive species.

Galapagos is also extraordinary because of the unique experience one has while visiting it. Because it was so isolated for so long, Galapagos wildlife never developed a fear of humans. In the Amazon, it's nearly impossible to see large animals such as a jaguar, whereas in Galapagos you need to watch your step or you may inadvertently tread on native wildlife!